In the late 1980’s the founder of Anatomic Research, Frampton Ellis, began what became pioneering research into footwear sole design based on the barefoot and its natural biomechanical properties, particularly as compared to conventional footwear. This was done more than two decades before the best selling barefoot running book, Born to Run©, was published or the Vibram Five Fingers™ “barefoot” running shoes introduced, and almost as long before Nike Free™ “barefoot” design shoes where introduced, as well as the multitude of other barefoot and minimalist shoe designs so widespread today.

As is often the case in invention, the starting point for his work was a casual, impromptu personal experiment that seemed trivial at first, but took on great significance as the research progressed.

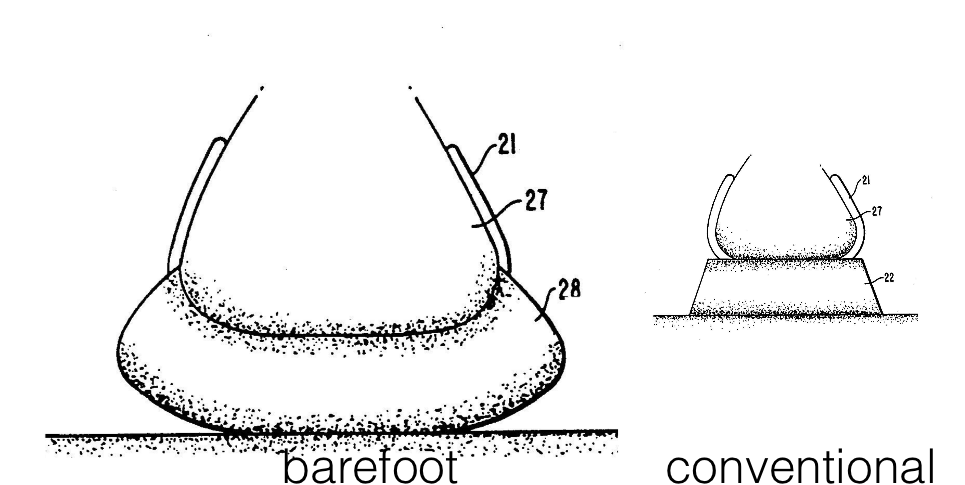

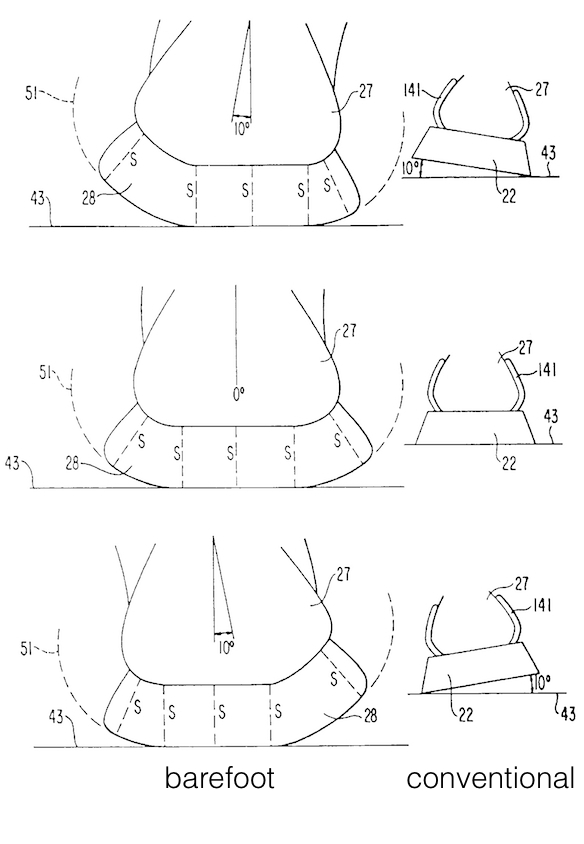

The ad hoc experiment consisted simply of nothing more than rolling a bare foot outward on the ground while standing still and upright. In this position the bare foot was perfectly stable, even while supporting half or even a full body weight, with a wide base at the heel (see barefoot picture below).

The stability of the barefoot was a surprise. What stood out, so to speak, was that the same foot, when shod with conventional footwear, is highly unstable in same tilted outward position. With shoes, at first you teeter on the angular edge of the shoe sole and then your foot rolls uncontrollably to the outside (see shoe picture below).

With a little research it turned out that nearly all ankle sprains occur in this tilted out position. Such inversion ankle sprains are by far the most common sports injury and also the most frequent cause of hospital emergency room visits. Besides these acute ankle injuries, chronic running injuries appeared to be related to rolling the foot in the opposite direction to the inside, a pronation motion of the foot that is excessive with conventional footwear.

With this information it appeared to Frampton that the lateral instability of conventional footwear was both inherent and a serious problem, and that the solution was to redesign the sole of footwear so as to preserve the natural stability of the barefoot. Basically, to be natural, he determined that the shoe sole had to be contoured to the curved shape of the human foot sole, not like a flat cookie-cutter section of the ground like conventional shoe soles.

The barefoot shoe sole design Frampton came up with has four essential elements: first, greater width, to match the wide load-bearing portions of the barefoot sole throughout its full range of motion, from maximum pronation to maximum supination; second, a rounded shape, to parallel the curved shape of the human foot; third, greater flexibility, to parallel the rounded human foot’s capacity to flatten easily under body weight; and fourth, uniform thickness in the frontal plane, so that the barefoot remains in a neutral position when it moves sideways on the shoe sole, just as if it were directly on the ground (see picture below).

So in early 1988 Frampton began what became a multiyear process to develop his new barefoot shoe sole design, while at the same time working full time with the Federal Government. The development process involved experimentation with various rudimentary shoe sole prototypes, particularly running shoes, first testing on himself and then with athletes, some of whom were world class runners.

He also began developing and filing patent applications, both in the U.S. and internationally. [Anatomic Research Inc. Patents] In addition, he met with the leading researchers in footwear biomechanics, both in the U.S. and abroad.

During this period Frampton was successful in attracting a considerable amount of print media and television attention, including a feature in THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. But even with the many resulting contacts, no license or manufacturing offers could be finalized into a reasonable commercial deal by the end of 1992.

At the beginning of 1993, Frampton focused primarily on developing a professionally made engineering prototype of his design for a court shoe, like a basketball or tennis shoe. That effort was both extremely expensive and time-consuming, but finally yielded a prototype (right foot only) that could be tested against existing footwear.

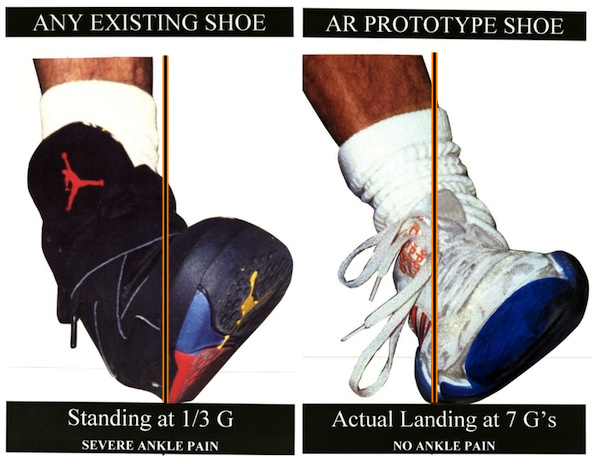

The testing was done professionally at a leading university biomechanics lab by a former director of research at Nike who was at that time consulting for adidas. The results were quite good for conventional tests, but were especially striking for an entirely new test that Frampton devised to highlight the entirely new level of performance made possible by his new barefoot shoe sole design.

In the test, student volunteers were instructed to jump while standing as high as they could and then land only on the prototype-shod foot while at the same time holding that foot tilted out in the inversion ankle spraining position.

With a conventional shoe sole, that is impossible to do without a severe lateral ankle sprain or break. Without even jumping, when only standing, severe ankle pain is experienced at only about a third of body weight (G).

In dramatic contrast, student volunteers equipped with the prototype barefoot shoe sole could jump high and land at G forces as high as 7 G’s with no ankle pain (as shown in the photographs below).

The test results led directly to a referral by the adidas consultant to the head of R&D at adidas. That led immediately to extensive licensing discussions that went on for almost an entire year. During that year Frampton also had some early stage licensing discussions with Nike.

In addition, he initiated a pre-production prototype development program as the next step to manufacturing and marketing the barefoot shoe sole design, in case licensing discussions with adidas and Nike were not successful.